Key findings

Note: these figures are correct as of July 2023. The data may have been updated since.

In the UK since 1600, we estimate approximately 12,500-13,800 public representational monuments have been built, plus at least 1.8m funereal monuments. A significant portion of these have links, of various kinds, to British transatlantic slavery. To date (July 2023), we have identified 872 British representational public monuments related to transatlantic slavery. There are likely significant numbers of additional monuments to be found, mainly in the form of funereal monuments in churches and graveyards, and (to a lesser extent) in British monuments with links to slavery in North America.

Below are some of our key findings. Please see the bottom of this page for our typologies and definitions, if you are interested in what is and isn’t included in this survey.

Monuments connecting historic sites

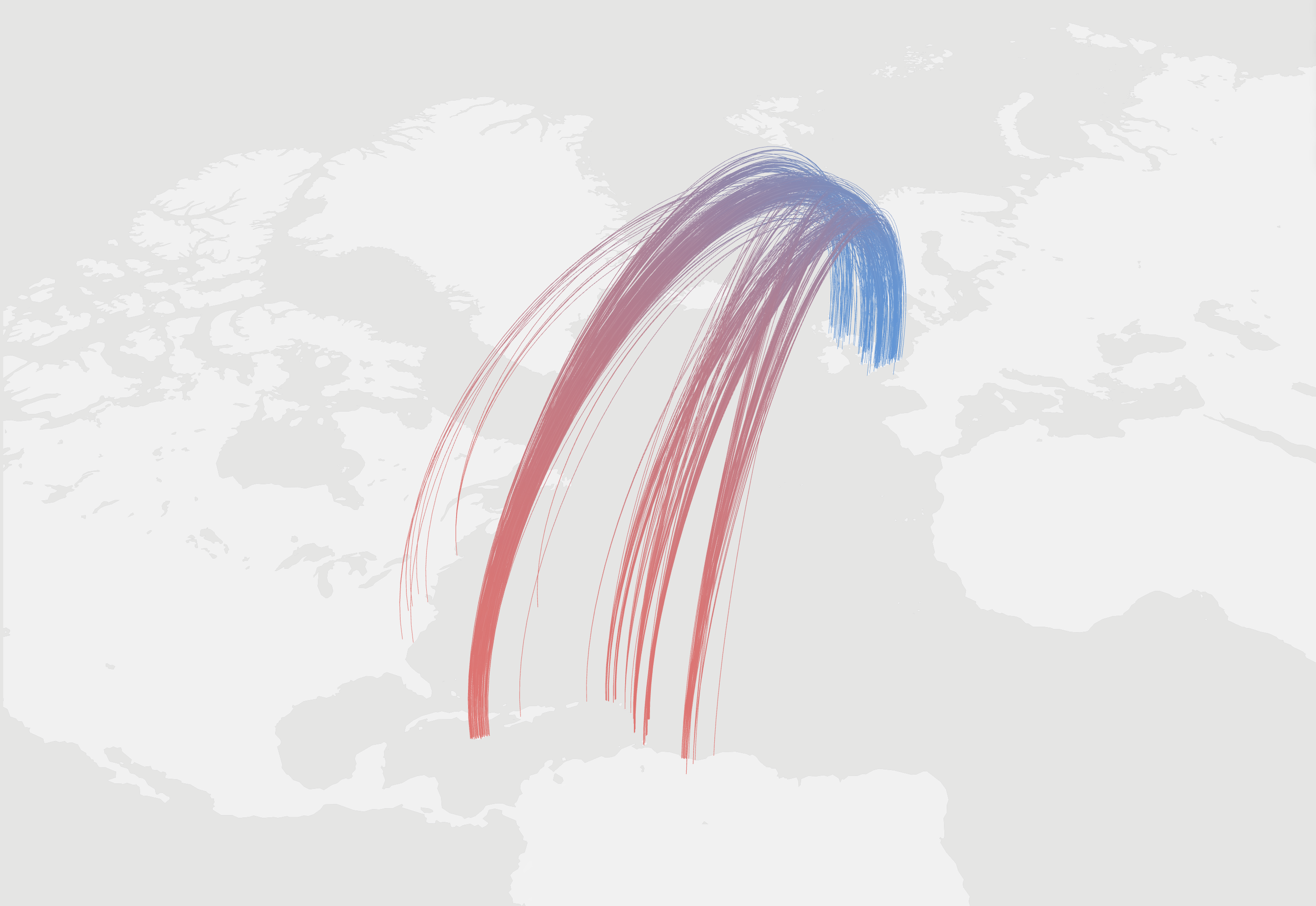

In the UK, slavery was often unseen, as the work and lives of enslaved people mostly occurred far away, in sites like Caribbean plantations or African slave forts. However, multiple UK monuments can be linked to specific plantations. These monuments that define social spaces in the UK are also markers of distant heritage sites of the British practice of slavery.

The monuments are connected to plantations via the people who funded, or are represented by, these monuments, and the plantations those people owned. Most of the linked monuments connect to plantations in Barbados and Jamaica, which held the largest British-owned populations of enslaved people, while the rest link to other colonial plantation sites. Viewed in total, these links evoke the final leg of slavery’s ‘triangular trade’, in which commodities and profits are extracted back to the UK. Cumulatively these monuments are memorials illustrating the circuit of transatlantic slavery’s primitive accumulation.

The sum of British public representational monuments’ links to former plantation sites.

Monuments’ types of relation to transatlantic slavery

The relationships to slavery recorded in this data are of multiple types. They include slave-ownership, slave-trading, abolitionism and uprisings of enslaved people (including both large-scale uprisings and the individual revolt of escapees from slavery). 726 of the monuments represent specific people linked to slavery (in words or figuration). It is worth noting that those monuments were not necessarily erected by those people.

Meanwhile, we note relations of profit from, or management of, slavery in multiple forms. 537 monuments are linked to slave-ownership, 78 to slave-trading, and 52 to the governmental administration of slavery. Others are direct beneficiaries (immediate family or legal beneficiaries of the above).

Monuments of recognition and opposition

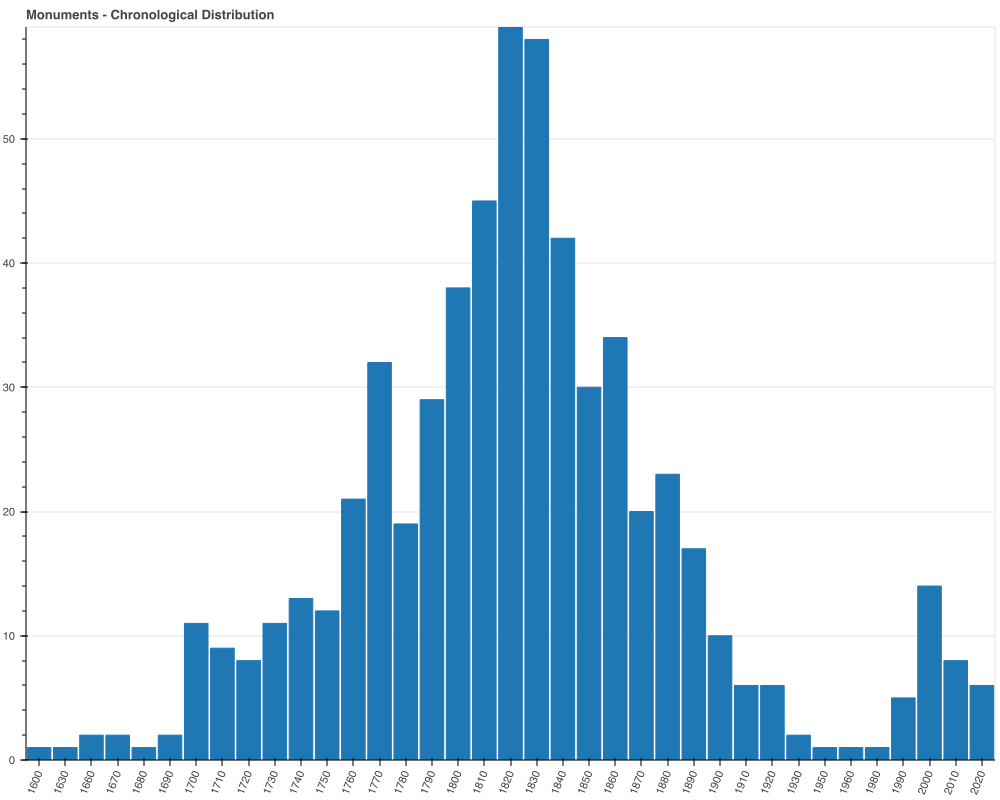

One of the notable patterns in these monuments is that of omission. The twentieth century is marked by a striking silence among British monuments regarding slavery. No monuments marked the 1907 and 1933 abolition centenaries. There are 40 monuments to named historical enslaved people between 1701-1887, all funereal. There is then a 110-year gap before any further monuments to historical enslaved people as named individuals or as a group, until a small 1997 plaque on the side of a local museum in Bristol. This small sign is also the first monument simply acknowledging British responsibility for transatlantic slavery.

There are similar omissions in the ways opposition to slavery is represented monumentally. Between 1807 and 1881 there was a wave of white abolitionist monument mania. These are monuments to white British abolitionists which tend to represent abolition in uncomplicated nationalist terms as the moral triumph of a small group of British parliamentarians’ enlightened benevolence, led by pure motives. Such monuments do not remember the culpability of some abolitionists in slavery itself or their missionary motivations; considerations of other historical reasons why slavery ended; or the various forms of black abolitionist agency.

17 monuments represent black abolitionists. Almost all of these have been put up thanks to the efforts of black-led grassroots campaigns, in two recent waves from 2007-2011 and 2014-2022.

Britain still has no intentional monuments remembering the agency of slave revolts and their rebel leaders - unlike, for example, Haiti or Barbados. However, 36 further British monuments can be linked to the sites and events of different slave uprisings, from organised collective revolts to daring individual escapes, whose deeds and names might also be remembered in stone. These can be found through the search function on the map page. We are currently prioritising expanding this aspect of the site.

Monument types and significance

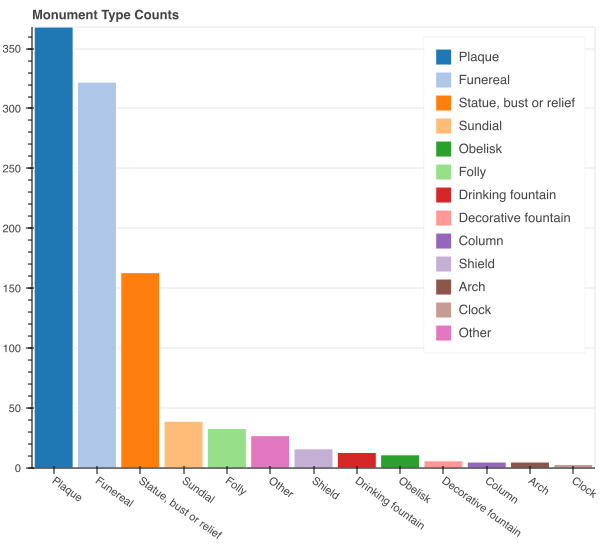

Nationally we identified 214 slavery-related statues, busts or reliefs. 119 of these are linked to specific instances of slave-ownership or trading. Statues have been a focus of public debate partly because they are often located in highly populated urban areas, and have a clear function as propaganda art. But they are not Britain’s most numerous type of monument related to slavery.

Funerary monuments (tombs or mausoleums, gravestones, and plaques inside churches - 349) and plaques (419) are the most numerous. There are 297 and 304 of these linked to specific instances of slave-ownership or trading, respectively. Given the lack of data on funerary inscriptions and on small-scale slaveowner biographies, and the many funerary monuments in the UK, it is likely that there are thousands more undiscovered funerary monuments linked to slavery. This makes funerary monuments the UK’s most numerous monumental form of slavery heritage.

However, the map on this site belies the fact that the significance of these monuments is not only a matter of frequency or location. For example, even when there is a connection between a monument and slave-ownership, the directness of that connection may vary. For example, most plaques related to slave-ownership are not extant heritage of that person’s life, but erected much later. Most plaques were erected after 1900 (London’s blue plaque scheme began in 1866). There are far fewer follies and stained-glass windows related to slavery. But these usually embody a more direct financial relation; larger single investments in slavery; and more often are an index of the inclinations of an individual.

If we consider monuments which were erected by slave-owners, traders and other beneficiaries of slavery, in which they also most-frequently represent themselves, then it is arguable that the funerary monuments have a leading significance as monuments related to slavery. Funerary monuments of the eighteenth and nineteenth were also very regularly intended as an assertion of class status and ideological values, as well as expressions of personal affection.

Custodians

Who is responsible for these monuments today? Given the large number of funerary monuments, the single largest institutional custodians with responsibility for British slavery-related monuments are British churches, predominantly the Church of England (once a major slaveowner in its own right). Roughly 480 of the monuments we identified are listed or scheduled, making national heritage bodies the second largest custodian. The diffuse regional plaque schemes are together a third major organisational custodian.

British slavery-related public representational monuments in our data by type.

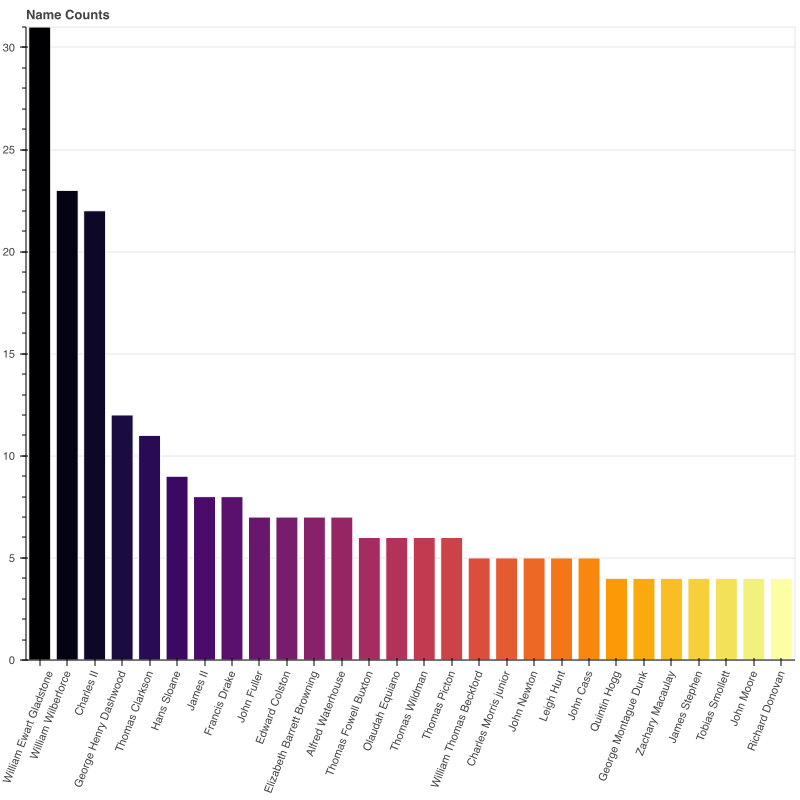

British slavery-related public representational monuments by associated name.

Representations of enslaved people

Allegory and myth are the most usual way in which enslaved people appear through monuments. Personifications of Africa as a woman or cherub bearing gifts do not necessarily depict slaves so much as allegorise colonial extraction generally, but such monuments obscured and normalised slavery, and may have been interpreted as images of slaves. We identified 8 such personifications pre- and post-abolition, mainly on pediments and entablatures of finance, trade and government buildings. Other monuments legible as slaves are ‘blackamoor’ heads, not least on the crests of the Royal Africa Company or slave-traders John Hawkins or Duncan Darroch. These have an independent iconographic history from the late 1200s, but their frequency and reception changed under British colonialism. We identified 20, many no longer extant. Both iconographic heads and personifications of Africa are not well-recorded and there are likely more. We identified 48 clear allegorical representations of transatlantic slavery itself, including unspecific text describing ‘slaves’; representations of black people in bondage; and other metaphors including chains. 32 monuments use kneeling slaves as secondary figures. Of these, 26 are garden ornaments, mostly of 1701-1748, portraying a blackamoor ‘slave’ supporting a sundial. The overwhelming majority of these allegorical representations adopt a broadly neoclassical style.

Conclusions

For many monuments in our data, a link to slavery is identified for the first time. Few could claim to be individually significant financial legacies of slavery (compared, for example, to the building of country houses). Their significance arises when seen in aggregate, for the scale and patterns revealed. Seen together, they provide one more cultural index of the heritages of slavery.

Statistically, British public space is symbolically dominated today by monuments related to advertising, war, colonialism and slavery. But that of these, monuments with links to slavery make up a relatively small number of the total. Yet these monuments retain an extraordinarily unique, intense significance only lightly addressed by their legal custodians, who have focused on celebrating (a simplified vision of) ‘white abolition’ over acknowledging slavery and its legacies or remembering black agency. Where new public understanding and changes to these propaganda monuments have occurred, it is so far predominantly thanks to the work and pressure of black-led grassroots campaigns.

A more in-depth, academic report on our findings can be found here:

Typologies and limits

Representational monuments included objects such as statues, busts and reliefs; blue and other plaques; funerary monuments like gravestones and church plaques; coats of arms; or other monuments including text or symbolic elements. We have erred on the side of including borderline ‘representational’ objects such as follies, clocks, decorative fountains and drinking fountains. We have excluded full buildings, designed objects lacking representational aspects (eg. railings); outmoded functional objects (eg. cannons); or indexical representations (eg. milemarkers). Due to paucity of data, we exclude shop signs of the 1600s, which commonly figured images of Africans inferable as slaves, mostly removed by municipal improvement boards in the 1700s. We similarly exclude pub signs, including those representing General Thomas Picton in Newport, Porthcawl and Nantyffyllon; William Beckford in Salisbury and Tewkesbury; the blackamoor at the Green Man, Ashbourne; or the 30 extant pubs named ‘Black Boy’ or ‘Blackamore’.

Public monuments includes those in public social space (in outside space, but also those inside publicly accessible buildings including council and school premises). For clarity regarding the propagandist function of these objects outside the particular ‘art world’ of fine art, we excluded ‘public collections’ of sculptures in museums, which are also not necessarily on permanent public display. Our data also does not include British monuments related to slavery outside the UK, for example extant British monuments imported to former colonies by British plantation-owners.

Relations to slavery we have included connections to: slave-ownership; slave trading; claimants under the 1837 Slave Compensation Act; legal and immediate familial beneficiaries of slave-ownership and trading; and connections to abolitionist movement activism and to slave uprisings. We exclude monuments linked to merchants or industries that traded with plantations (eg. Robert Cary’s tomb; Bebington fountain; Robert Owen statues); to ideological supporters of slavery without financial connections (eg. Nelson; William Lamb; Richard Hooker); to the foundation of colonies that became plantation-sites (eg. Virginia expedition monuments; George Somers statues); or to indentured plantation labour which sought to plug the labour shortage left by abolition with minimal structural change (eg. Henry Tate’s bust and tomb).

The criteria are inclusive and often overlapping (AND/OR). A related person may be, for example, a slave-owner, trader and claimant under the 1837 act.

Claimant under the 1837 slave compensation act. our monument data simply follows the records of claimants in UCL’s Legacies of British Slavery data, which you should consult directly for more detailed information. Likewise our data on resident/absentee planter status follows the UCL data and is replicated here for purposes of filtering.

Direct beneficiary of slave-ownership. includes the above claimants, legal beneficiaries, and immediate family of slave-owners, traders or claimants.

White abolitionist is a distinction we make advisedly and critically. We note among white abolitionists were also slave owners, those with ambigious positions on the meaning of 'abolition,' or those drawn to abolition under one or another form of broadly missionary ideology.

Listed or scheduled monuments are recorded as listed when they are directly the subject of a listing, but also where the grounds or building they are in is listed. The listing records often do not include enough detail to mention specific monuments.

Located inside a church use this criteria to filter plaques for those which are funereal monuments mounted on the walls of churches. This criteria does not include monuments in the grounds or yards or churches.

Covered, modified or removed this criteria notes the date of any removal for any reason, but it is notable the majority of these occur in a continuing wave which follows the black lives matter movement.

Related Sites of Historic Slavery are most often plantation names, or occasionally other sites. Our downloadable .csv data also includes LAT/LONG coordinates for those sites. These are precise where possible, but when historic sites are not precisely known, these may simply indicate a region or an island. Where plantations are in the Caribbean, you may find them on the Legacy of British Slavery project’s maps of Jamaica, Grenada and Barbados. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/maps/caribbean/

Limits to the relations identified come in multiple forms. In relying at points on the Legacies of British Slavery data, our findings skew towards Caribbean plantations after 1763. There are likely a significant number of additional monuments linked to (pre- and post- American independence) plantations in America; to corporate ownership through, for example, the Royal Africa Company; to other sites of British slave-ownership and to British colonial governance and abetment of slavery. Whilst our analysis represents the most empirical picture presently possible, we are limited by these factors.